Where are the puddings of yesteryear?

Share Article

Go to a typical dinner party and you'll probably find a menu that is Mediterranean or Greek or Spanish. I love this food, but I get miffed when people imply that there was no cuisine before Canadians discovered fettucini, arroz verde, and Dijon mustard. Those of us who grew up in rural Canada at mid-century know that the cooking then—simple or exotic, sublime or stodgy— was just as satisfying.

"Oú sont les neiges d'antan?" long-ago poets sang as they lamented the passage of time and the world as they knew it. I've noticed the same elegiac note creeping into conversations with friends of my age. But instead of nostalgia for the snows of yesteryear—we still have plenty of those—we lament the passing of the homely joys of our mothers' cooking. Our plaint runs something like this: "Where are the puddings of yesteryear?"

In those days before lean cuisine became la mode and 'wellness' became a cult, there was always a pudding: tapioca puddings or fruit puddings with brown sugar toppings, or creamy custards. Many had homely names like apple betty, floating island or roly-poly, apt for a rib-hugging steamed suet pudding made with black currant jam.

But the acme of puddingdom was an unlikely mixture of carrots, potatoes, suet, raisins, currants, cherries and spices. It appeared for Christmas dinner, sometimes drenched in brandy, and always served with a rum and butter sauce and whipped cream. Afterwards it was absolutely necessary to find a sofa and put our bellies up for an hour.

No wonder my friends and I get nostalgic. Today's desserts, if in fact we are bold enough to defy public censure and eat one, are leaden layer cakes with puritanical labels like Chocolate Sin. Or there may be seditious sorbets that look pretty but assault the sinuses with blinding pain.

We also remember the fancy sandwiches for I.O.D.E. and church teas. Served on the requisite starched doily on a silver tray, they imparted a pleasant sense of haut monde.

We sat in the kitchen watching our mothers make these dainties, and we can still describe the fillings and the method, even at 40 years' remove. The bakeshop would provide bread, delicately tinted pink or green, and from this base would emerge ribbons filled with pineapple or pimento cream cheese and pinwheels stuffed with asparagus or gherkins. To achieve the highest degree of refinement, at least half of the bread, butter, and filling was cut away, and we kids got to eat these remnants.

Looking back, I'm appalled at what we took for granted. In the winter, my mother filled dozens of jars with grapefruit and orange marmalade. In the fall, she coped with jelly bags dripping in the kitchen and pickles simmering on the back burners.

It's the pickles I remember most. In September, every Canadian village smelled of vinegar and spices. There were bread and butter pickles that we ate for lunch, layered on homemade rolls. There was tomato mustard, a spicy curry sauce that we slathered over hot dogs, and that bore as much resemblance to salsa as a hybrid tea rose does to a dandelion. There were spiced pears and chutney, pickled watermelon rind and pepper relish, plum ketchup and nine-day pickles, so-called because they took that long to make.

Now, the crocks for those aromatic mixtures of vegetables, fruit and spices marinating have metamorphosed into petunia planters for the back porch.

Grocers nowadays stock their shelves with jams, jellies, marmalades, and relishes with labels that say "gourmet" "original," or "olde tyme." Don't be fooled. None of it tastes the way it used to.

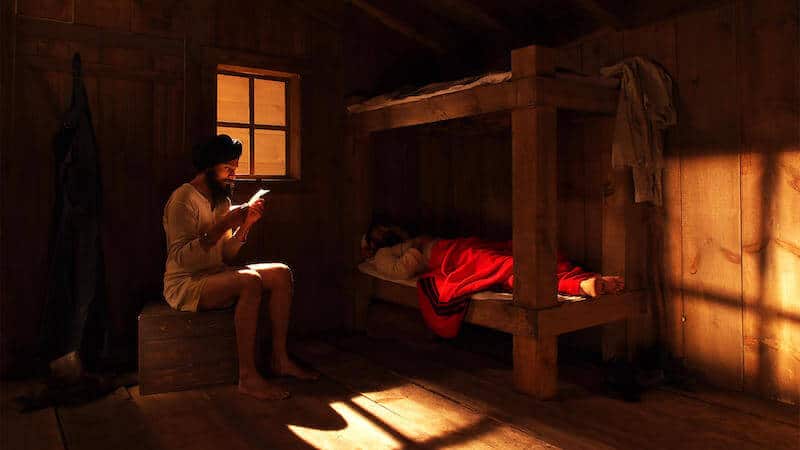

My mother's generation made no fuss about cooking. There were always chores to be done, and the cooking of three meals a day was one of them. Husbands and children in small towns came home for lunch and expected something substantial to see them through the afternoon. On farms, during the summer and fall, a small army of itinerant workers had to be fed. My Aunt Lillie, with whom I spent many of my childhood summers, made hot biscuits for these troops three times every day.

Last week, at a dinner party, I listened to a heated debate on the merits of tarragon or rosemary as a spice for poulet Provençal. I thought how foreign such a topic would have been at Aunt Lillie's table. She served up platters of delicious roast chicken with sage, onion and breadcrumb dressing, and we gulped it down, and that was that. To my shame, I don't remember ever complimenting her or offering to help with preparation.

Those were the days before cooking became a fashionable hobby. Even I, a reluctant cook who could not prepare three meals a day if my life depended on it, can count eight cookbooks on my shelf. My mother had only one, Nellie Lyle Pattinson's Canadian Cook Book. Looking through the detailed information on its bespattered pages, I realize its value to the bride of half-a-century ago who found herself cooking endless meals in an ill-equipped kitchen long before the days of gourmet mixes, corner delicatessens, and trendy restaurants.

Swapping of recipes was a necessary supplement to the basic cookbook. Experienced cooks passed on their expertise to novices. My mother's cookbook is filled with scraps of paper and file cards on which are written "Hannah's Cookies," "Ruth Morgan's Fruitcake," "Aunt Lillie's Tea Biscuits"—usually in the giver's own hand-writing.

A few years ago, my mother discovered an alternative lifestyle. She now orders in regularly from pizza parlours and chicken chalets. She's also learned to eat with gusto the pasta dishes that my son concocts, and has been known to order up a stir fry when we dine out. She has laid Nellie Lyle Pattinson to rest in the kitchen drawer, along with all her starched and neatly ironed aprons.

But my family misses her cooking. When we came up from the city to her house on Friday nights, there was always a wonderful dinner waiting for us: perhaps stuffed spareribs, butternut squash, scalloped potatoes, a favourite jellied cream cheese and strawberry salad, and a rich maple cream pudding.

My sons sometimes ask, "Mom, what family specialty will you serve our kids when we bring them to see you?" I honestly don't know. Maybe I'll resurrect Nellie Lyle Pattinson. At the moment, my hot biscuits are good little cannonballs, but I've learned to make tapioca pudding. There's a big call for it at our house when my sons are stressed out with university tests and essays. Let today's cooks jaw on about the low-fat joys of vegetable stir fry and fruit sorbet. For spiritual comfort and solid sustenance, there was nothing like a savoury roast and an old-fashioned pud.