Chandralekha

New Directions in Indian DanceShare Article

It could be the excitement—the week-long event is the first of its kind in Toronto and thanks to two years of dedicated work by producers Sudha Thakkar Khandwani and Professor Rakesh Thakkar—it's very well-attended.

Indian female beauty: jewelled, graceful, with kohl-rimmed eyes, brows each like the bow of Krishna, and face coyly beckoning. She wears garlands of flowers braided into her hair and yards of bells wrapped tightly around her lower legs. Her hands, with red-painted fingers, are held stiffly and often stretch into poses that have been used for centuries to represent a deer leaping through a forest, for example, or a lotus opening and swaying in the breeze.

As with any dance form, Bharatanatyam can be appreciated on some level by a novice onlooker for the agility and stamina required for complex steps, the discipline that keeps the effort hidden from the audience, and movements or gestures that appear original, interesting, or particularly beautiful. But as a language of dance, Bharatanatyam is full of polysyllabic codes that require study to allow full appreciation of its meaning.

Later that evening I watch a performance made up of simpler phrases. In Sri, performed by India's Chandralekha Group, the images are many that all derive from a few, carefully expressed 'words.' Their slow articulation and constant repetition allow meanings to metamorphose, as they do in the rereading of great poetry.

There are two legs, upside-down and illuminated by a stage light. For several minutes they remain poised there as if pulled up from the body by an invisible hand. They begin to move, barely, as if awakening. You cannot see the body, but catch a glimpse of a simple shift or shirt of a deep plum colour. The Premiere Dance Theatre is silent. There is no music, no beat, no voice. The knees bend slightly, and ever so slowly the feet begin to rub together, first one in front, then the other. Sensual without being erotic. The whole audience seems hypnotized, so intense are these smallest of small movements. But the movements are not stingy; there is no sense of 'What is this? Did I get all worked up to see some invisible person do a shoulder stand and wiggle his feet?' (for by now we are quite convinced it is a man). Instead, the grand leaps and twirls of classical ballet—whose dancers frequently jet into celebrity status outside the dance world, which perhaps helps explain why ballet is such a familiar dance form in North America—now seems bombastic. These movements are just enough—full but not overblown. You wonder if the dark stage and single spotlight have tricked your eyes: the feet seem to transform into the heads of two animals—giraffes?— nudging each other. You blink and the legs are now lilies, graceful in a breeze. The image of flowers remains as the legs part and come down to rest on either side of the head. And suddenly you know it's a woman; the pose is so like birth somehow. The piece ends... was it ten minutes long or half an hour? It doesn't matter. The lights dim and the performer comes into the spotlight: small, a warm smile, the pure white hair shocking as a frame for an unlined face. A woman. Chandralekha.

The serenity and power of this simple prologue succinctly demonstrates why Chandralekha is often described as 'the most radical choreographer in India.' Here, her minimalist style distils from dance what many would consider it's most rudimentary physical element: the legs. But hovering in the air as they do in the shoulder stand, with no ground to brace them, the legs mutely pay homage to two sources of power from which they extend and from which dance is born—the back and the breath—as well as to one source cultivated by yoga—the mind cleared of distraction and tension.

The tone is set for the rest of the performance. Simple without being stark serene and yet very much of this world. The sound of one stone hitting another begins an unembellished rhythm. The six female dancers are wearing cotton saris in muted earthy colours that remind me of food (mustard, bean). They are completely unadorned except for some simple dark bangles—no make up at all, no flowers, no shiny fabrics, no painted fingers or jewels. Unencumbered with the come-hither glances and smiles that help to hold Bharatanatyam in focus, their faces radiate individually. Their proud, upright postures remain unrocked by the quintessentially Indian gesture that isolates the head from the neck. The focus seems inward, without any attempt to charm, beckon, or express mock anger or happiness.

The first section derives from prehistory. A series of poses inspired by 'Matrika'—female fertility statues made from stone and clay that are still found in India—flow into confrontational positions and movements that have their source in martial arts. Another section in which a seventh dancer joins in, the only man, depicts a courtship. The man and one woman dance close together, looking each other straight in the eye. Their movements are equally decisive and strong. Three others lie in a circle around them with their feet together and knees on the floor, and begin to move their hips and legs in ways reminiscent of the birthing gestures of the prologue. The rest of the dancers join in and there is a joyous celebration. Suddenly the man reaches down, as if to touch the woman's foot in respect. But instead, he gently guides her foot towards him. Turning his back to her, he begins to trace a slow, small circle with his footsteps, his posture growing straight and then extending into a triumphant pose, allowing his gaze to move higher until it finally fixes on some lofty and distant point. The woman, in the meantime, has followed the same small circle close behind him, while her gaze and posture slowly drop in antithesis to her new husband's, until her back is curved down, and she stares at the floor.

What Theatre Fakes, Dance Does Real.

The next section is lively with interesting patterns of collective movement. When the group runs across the stage, the grand sweep is as refreshing as a ride on a swing. Feet pound out strong beats. High kicks are absorbed back into a seated half-crouch, the kicked leg bent to the side, foot flat on the floor, the other leg extended. Later the women crouch down on their heels, knees impossibly wide apart to allow their hands to reach out in careful, sweeping gestures low to the floor. Are they spreading grain to dry? Washing the floor? The gestures are evocative but not realistic; surely having knees on the floor would be a more natural position, greatly easing the difficulty of the movement.

The movements throughout the performance are extremely intense, yet there is never any sign of strain. The contained energy blossoms through every move, no matter how slow or simple. Nothing is done carelessly. Chandralekha insists on making sure that dancers don't 'fake it.' The movements have to be internalized so that the audience is engaged. This is why the result is mesmerizing; the group is not merely putting on a show by going through the motions.

These are women dancing as real women, not swans, fairy princesses, or perpetually waiting lovers. It's as if being just a woman is not enough in ballet—you have to conform to the shape of some fantastic bird with the elongated neck of a great egret the legs of a stork, and the humanly unnatural lightness of a hovering hummingbird. And if balancing yourself on a few square inches of toe isn't enough, an equally fantastic man has to come along and hoist you up into the air.

Their peacefulness and confidence is striking. When their gazes meet or cross, they look directly in each other's eyes with no change of expression, as if they can see within the other a reflection of themselves. It is a variation on a common element in traditional Indian dance: the dancer transcends the effort of the physical movement and seems the very epitome of grace and tranquillity. An eye of peace in the whirlwind of choreography.

The short epilogue to the programme layers a multitude of codes from traditional dance. The dancers, one behind the other, extend arms and legs in a multi-limbed array of poses. These are held for a moment and then extended, fingers blossoming open. The final, breathtaking result is, in Chandralekha's own words,

...a vision of the future

an iconic vision of woman

who is both auspicious

beautiful

luminous

and empowered

who is both Sri and Durga

with multiple hands

with multiple capacities

with multiple energies

DASHABUJA—with ten hands

who can change all space

who can charge all space

it is the vision of the future woman.

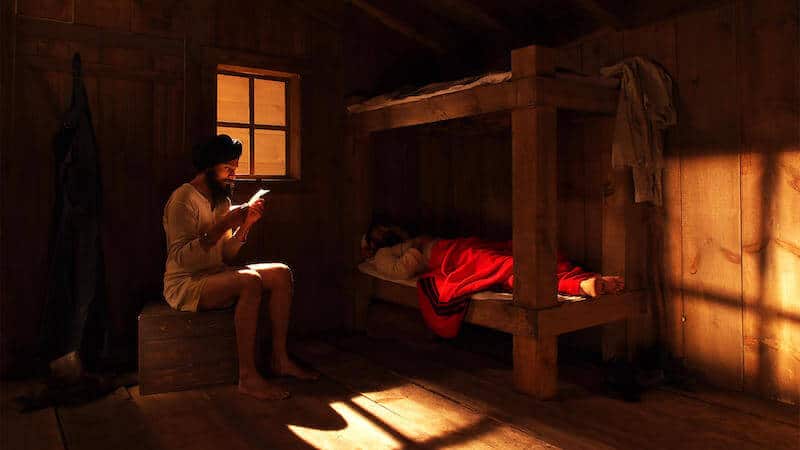

The next morning, so moved by the performance, I go again to Harbourfront to hear her speak. As Chandralekha points out, "What theatre fakes, dance does real." Take for example, the 'drag walk' of the final section of the performance from the previous night. The dancers move across the stage, as shown in the photo, bent at the hips and knees, their feet dragging slowly while remaining flat on the floor throughout. It's a difficult move that begs for relief by at least allowing the back to curve down, and the head and arms to fall. But what an oppressed image would result! Instead, the dancers lift their heads to look forward in a way that is vulnerable, defiant, and much more 'backbreaking' than the more realistic, curved back position would be.

Among the many things she talks about—in refreshing, non-academic terms—is the flow between life and dance: 'There are no compartments between [them]...the principles of work are the same as the principles of dance.' Suddenly she jumps up from her seat at the long conference table on stage to demonstrate what she means. "Say you are cooking in the kitchen..." A spontaneous Mustard Seed Dance emerges! You can see the hot stove by the way she holds the drape of her sari back to avoid having it catch flame; you can almost hear the insistent spit and crackle of the heated oil threatening to burn if she doesn't pay attention to it now; you understand the way her body contracts and virtually hops about in the effort to work as quickly as possible, while her hand pecks like a bird to pick up the different spices and drop them into the pot. You can hear the mustard seeds pop as they absorb the heat of the oil; in fact, you almost begin to smell the curry. "Performance," she says, settling back into her seat, the kitchen disappearing as we stare at this delightful woman, open-mouthed, "can happen or not. It's a secondary thing."