Selling Bob Marley

One Love Experience reviewed

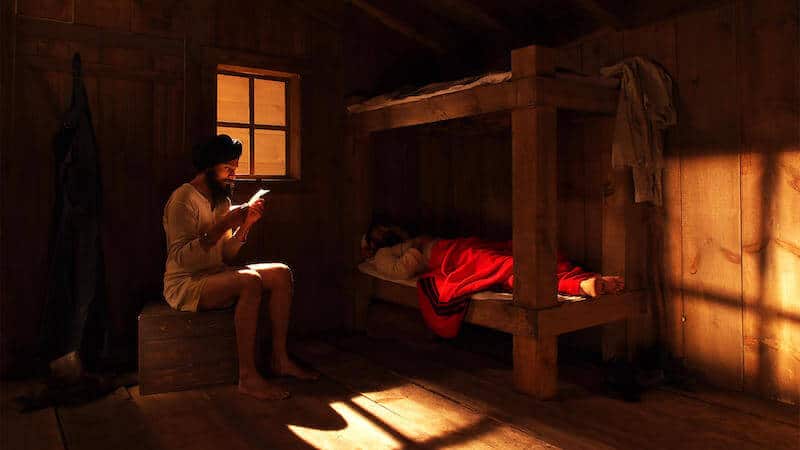

© Alex Brenner, Bob Marley One Love Experience, the Concrete Jungle Street Art Expo at Saatchi Gallery.

Bob Marley - One Love Experience

Lighthouse Artspace

Toronto, Ontario

Summer 2022

Share Article

On July 1, 2022, The One Love Experience opened its doors, profiling the life, legacy, and lineage of Bob Marley. Growing up on his music and image, I have always known Bob as a Rasta, an unapologetic anti-capitalist with an untameable mane, strumming the machine that stays aimed at the sheriff.

The first room – the “One Love Music Room” – included some familiar iconography: diamond, platinum, and gold-selling records by Bob Marley and the Wailers. Immediately I felt I was being introduced to a musician, to someone being marketed to me via iTunes. The packaging broke the fourth wall and made its commoditization too obvious. I looked at the records that formed my childhood mythos, missing the natural mystic that Bob came from, the Jamaica that shaped him, the roots that made Bob rock. The experience started at the end.

Filled with creative interpretations of Marley’s legendary contributions to reggae music, the space displayed graffiti, collages, replicas, and memorabilia of his time on tour. Curated in collaboration with Cedella Marley of Marley’s estate, there was a “street” element to the rooms: the blackened walls, vibrant paint, and repeating reassurance to take selfies diluted any “gallery” feel and heightened the “packaged” quality. Like when Dove makes cocoa butter body lotion and sells it in shiny brown bottles, as if otherwise we wouldn’t know we are their target audience. The strategy was too obvious to hold any immersive power.

The "One Love Forest" was the next room of the immersive Bob Marley experience, with walls covered in plastic foliage (including cannabis leaves), a soundtrack of jungle sounds, a picture of Dunn's River Falls with "Every Little Thing Gonna Be Alright" transcribed across the top, portraits of Marley smoking herb, and a neon "LIGHT UP" sign accented with selfie props such as a cut-out Lion of Judah and sunglasses. Too few were mentions or memorabilia of Rasta culture or Rastafarian beliefs. Too few were mentions of how Bob found his religion, and how herb, nature, plants, water, sunlight, and storms were infused in his music. I thought of the heavy bass that comes right after Bob coolly warns "there's a natural mystic blowing through the air" or reminisces "Cold ground was my bed last night/And rock was my pillow, too." I was unacquainted with the rockstar or Ganja God portrayal of Bob Marley. My mythos of him is as a man who meditated, elevating his consciousness high enough to rebel against oppression and remain firm in his pan-African purpose. For 40 years, any effort to make him Robert has been challenged by his cultural significance as Bob.

The show was located at the Lighthouse Artspace at 1 Yonge Street, a landmark to Toronto, and it felt like it. The experience felt like a diluted shadow of where Black people used to live and work. The replicas created such a lacuna, such simulacra, that I felt more immersed in his loss than in his life. There was no pulse to rebel or to rock steady. The tone was as though Bob’s work was done and now it is time to smile. The importance of Bob Marley on my life has been a constant soundtrack for remembering who I am in a world that would rather I not know, designed for me to systemically forget. The trace of what we have lost reminds us that there is something worth preserving. I felt determined to remember.

We were given headphones to walk through the Soul Shakedown Studio – a space of replica road cases and video of a concert playing against the far wall. One of the setlists affixed to a case was of Bob's performance at Toronto's Massey Hall on June 8, 1975. Noticing that the setlist mistakenly says "Massey Hill," instead of the state-of-the-art stage known as Massey Hall, I couldn't help but feel like being in a segregated city: a hall for the haves, and a hill for the have-nots. But for those of us already enveloped in the counterculture, it also felt like a welcome misrepresentation. A private joke among contrarians.

We walked through "The Beautiful Life" room that showcased some of Bob's most loved pastimes, as well as the "Concrete Jungle Fan Art Exhibition" which heavily profiled the work of painter Mr. Brainwash. Meanwhile, Survival, arguably Bob's most politically charged album, was front of mind for me as the exhibition displayed ping pong and soccer as Marley's beloved hobbies. Loving ballads such as "Turn Your Lights Down Low" and "Is This Love," showcase the radical as a revolutionary lover. He was also a fighter. "Africa Unite" pulsed through my mind while witnessing all the artistry Bob Marley's legacy continues to inspire, and it made me want to take to the streets of Eglinton Avenue West to be among community.

In the final room of the exhibition, a friend and I spoke of idolatry. It was clear. The lasting impression of Bob Marley belongs to the people; it is ours to create, to critique, and to hold dear. The DNA of that legacy is both, at the same time, the mother strain of elevating him, and daughter strain of keeping him grounded. I'll take the iconoclastic work of always resurrecting Bob Marley's quotes, including his famous last words: "Money can't buy life."

Much like cool neighbourhoods that gentrify and push out creative communities, there seemed to be two Marleys present: the rockstar, and the Rasta. I felt twisted about having purchased VIP tickets to the commercialization of Bob Marley. My yearning to be in a moment with him highlighted that only the experiences of imitations of him were available. The plastic flora of the “One Love Forest,” or the headphones in the "Soul Shakedown Studio" extracted more than it planted. I returned to my work of finding art and culture that provides community outside of ticket sales. I went back into my community.