Prickly Fruit

The Orchard (After Chekhov) reviewedThe Orchard (After Checkhov)

Written by Sarena Parmar

Directed by Jovanni Sy

March 21–April 21, 2019

Arts Club – Stanley Industrial Alliance Stage, Vancouver, BC

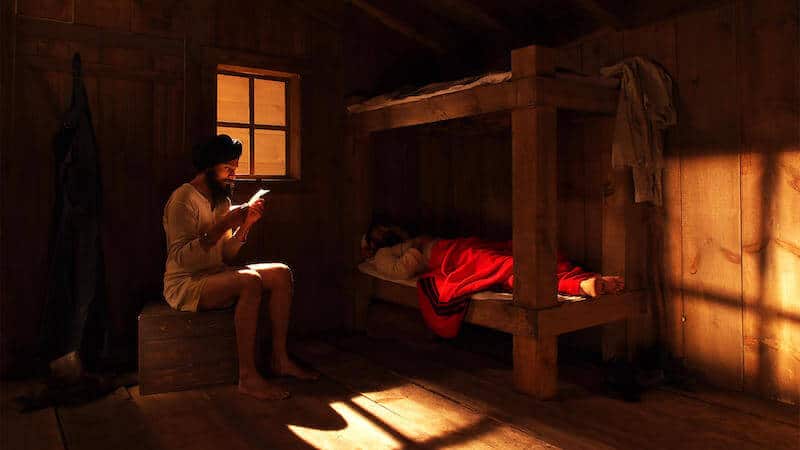

The cast. Set design by Marshall McMahen, costume design by Barbara Clayden, and lighting design by Sophie Tang. Photo by David Cooper.

Share Article

"To a cowboy in love, it is a mandolin," declares Yebi (Kai Bradbury), a Japanese Canadian internment camp survivor and aspiring cowboy, brandishing his acoustic guitar. In this comedic register verging on high melodrama, first-time playwright Sarena Parmar is at her best. The Orchard (After Chekhov), her adaptation of Anton Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, is set in the Okanagan in the early 1970s, on an orchard belonging to the Basrans, a second- and third-generation Punjabi Canadian farming family. When they are faced with losing the property, the Basrans' inaction forms the backdrop for poignant reflections on mourning and memory as the family struggles to come to terms with the end of an era at the orchard.

At the same time, The Orchard seems acutely aware of its own incongruities. As in Yebi's dream of being a cowboy, the humour of this adaptation lies in the absurdity of nostalgia for a tradition not entirely your own. His beloved cowboy boots squeak with every step despite his best efforts to play it cool, which got a good laugh out of the audience at my showing. The boots have their analogue in the somewhat awkward fit of Chekhov's tale of a declining aristocracy adapted to stage South Asian Canadian life in the 1970s. Calling attention to that mismatch, the play's secondary characters and divergences from the source material often have the greatest impact, especially in the compelling twist on the final scene.

Adele Noronha, Laara Sadiq, and Munish Sharma. Set design by Marshall McMahen, costume design by Barbara Clayden, and lighting design by Sophie Tang. Photo by David Cooper.

This Arts Club production, directed by Jovanni Sy, marks the second staging and Vancouver premiere of the show, originally played in the round at the 2018 Shaw Festival. In transposing The Cherry Orchard for the Okanagan, Parmar stakes her claim to a tradition of classical theatre that has historically made little room either for the experiences of Indigenous and racialized people in Canada or for the active participation of South Asian Canadian theatre-makers. She writes in her introductory notes in the program, "As much as this is a classic Russian play, as much as Canadian history is reflected as a European narrative, they are both also mine." Loveleen (Laara Sadiq), both prodigal daughter and Basran matriarch, dazzles in her first appearance onstage wearing an uncharacteristically glamourous magenta silk saree; in a resonant parallel with her aristocratic Russian counterpart in Chekhov, she has totally retreated into a world of fantasy.

Image credit: Rusaba Alam.

On the whole, less fidelity to Chekhov's original and a firmer directorial hand would have been welcome in a production running two hours and forty-five minutes. One scene, in which Yebi refers to his time in an internment camp and rodeo star Charlie (Andrea Menard) recounts her escape from a residential school, serves primarily to name the characters' identities for the audience. These threads might have been developed in greater depth to revise some aspects of Chekhov—like the pacing of events or the relationship of most of the secondary characters to the family drama—which are hard to explain in the contemporary setting. As it is, moments like Charlie's testimony, disconnected from the plot, stray into a tokenism that feels far from the playful spirit of Parmar's writing, which begs the question: what does it say about Canadian theatre today that a classic adaptation centering non-white experiences must constantly announce itself as such?

I wonder if the demands of producing and selling something called "South Asian theatre," especially at a mainstream company, and with an ambitious 13-character staging, account for the fairly rigid adherence to Chekhov's plotlines and the lapses into tokenistic representation. After all, the latter is a pitfall of which the play seems quite aware. When Yebi reveals that his family was interned on the site of Charlie's community's reserve, we feel the full irony of her response: "They wanted to put all the troublemakers in one place." It is a shame indeed if the same can be said today of the function of this kind of adaptation of the canon for mainstream Canadian theatre.

In spite of or perhaps as a result of these pressures, <em>The Orchard</em> marshals a tremendous amount of local talent, including a strong cast made up of a majority of racialized actors. All these troublemakers in a room together are a sign of what might yet be possible. With its smart sense of humour and its willingness to take on a giant of the theatre, this is a promising first offering from a new voice worth noting.