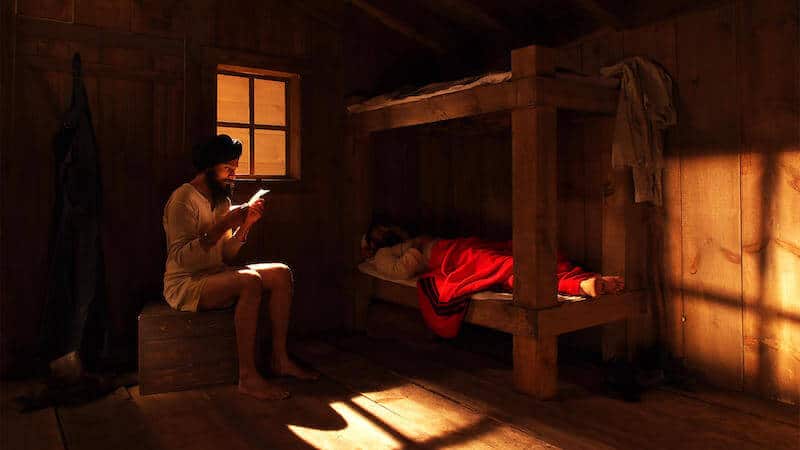

The first boat load of indentured labourers (coolies*) arrived in British Guiana (now called Guyana) in 1838 and from then on several thousand Indians crossed the 'Black Waters' (Kala Pani) to the new lands. ..Indians undertook the hazardous physical and spiritual journey for a variety of reasons. Lower caste Indians, sometimes existing in a state of virtual slavery in India, were glad to flee their landlords and creditors for the prospect of a new beginning...others were enticed by the fanciful tales of promises of plenty... Famine and civil war further swelled the number of indentures... The Indians occupied the old slave quarters and worked in the sugar plantations, inheriting many of the conditions of servitude of the previously enslaved Africans...

- Excerpt from India and the Caribbean, edited by David Dabydeen & Brinsley Samaroo

This is a version of the history of the country where I was born and lived until the age of twelve. My parents and I came to Canada in 1973. Immigrating at such a transitional age has left its scars on the psychic and psychological landscape of my personhood and sense of identity. I grew up in the predominantly white suburb of Mississauga with the experiences of living and surviving the racist era of Paki-bashing and a reactionary school system that streamed 'immigrant kids' The additional layer of grappling with sexual identity by acknowledging to myself and others that I thought I was lesbian, resulted in an even greater inner and outer exiled and marginal status.

For many the feelings of being exiled in a hostile landscape can originate out of a sense of geographical displacement. On a more profound level, the feelings of displacement and dislocation from self and community are linked to the immediate material (cultural, social and political) and psychological (internal exile) environment created in the minds of dislocated people.

It is crucial to recognize that the position one occupies as an exile (whose status is measured by the external environment) can and will shift, depending on the relations to the external, material environment. Furthermore, the notion of a psychological or internal sense of exile can shift and be replaced and redefined.

For many people of colour, the sense of an internal state of exile often represents distorted psyches, and a loss of self. This loss of self results from the experience, the legacies and the history of colonization. The construction of a race identity for people of colour is not static. A visible demarcation of race is the permanence of skin colour. The boundaries of self-expression are limitless and go beyond fixed notions of expected behaviour. When one lives in a racist culture and society, one's potential capacity and capabilities as a human being are explicitly and implicitly overdetermined by one's race. Some people of colour can succumb to the trap of believing that only certain ways of being or particular modes of expression are available to us. In an attempt to ease the pain of displacement, we often attempt to seek validation and belonging through external forces such as our communities, families, etc. It is undoubtedly a manifestation of the exile's quest for home, both within and without, which drives us to seek this validation and belonging. This search, however, should not minimize the fact that both community and family can be sites of our self-perpetuated struggles. The quest for self-actualization and centre is intertwined with romanticized ideals of home—the sense of belonging and security that is culturally and socially inscribed to notions of home. As people of colour, we need to redefine and reconstitute ourselves on our own terms via the necessary journey(ies) through our psychic and psychological terrains. We must leave the scars and legacies behind, but always be mindful of where and how we came to be— with a transformational vision of self and community.

For lesbians and gays of colour, the arena of sexuality is yet a further site of internal displacement. If skin colour is a visible demarcation of race, what then is a visible demarcation of a lesbian/gay identity? Part of my work as a filmmaker is to initiate and engage in a process of transforming the feelings of displacement and 'otherness' often experienced by lesbians and gays of colour. Film, then becomes the means by which both the filmmaker and audience can be engaged in such a process. The power of film lies in its ability to visually translate the complexities of what is both internal and external, visible and invisible in the lives of people.

*Coolies was once a neutral word for labourer, but is now used derogatorily to describe people of Indian ancestry in the Caribbean.