Beyond Extinction

Ali Kazimi documents Sinixt resurgence

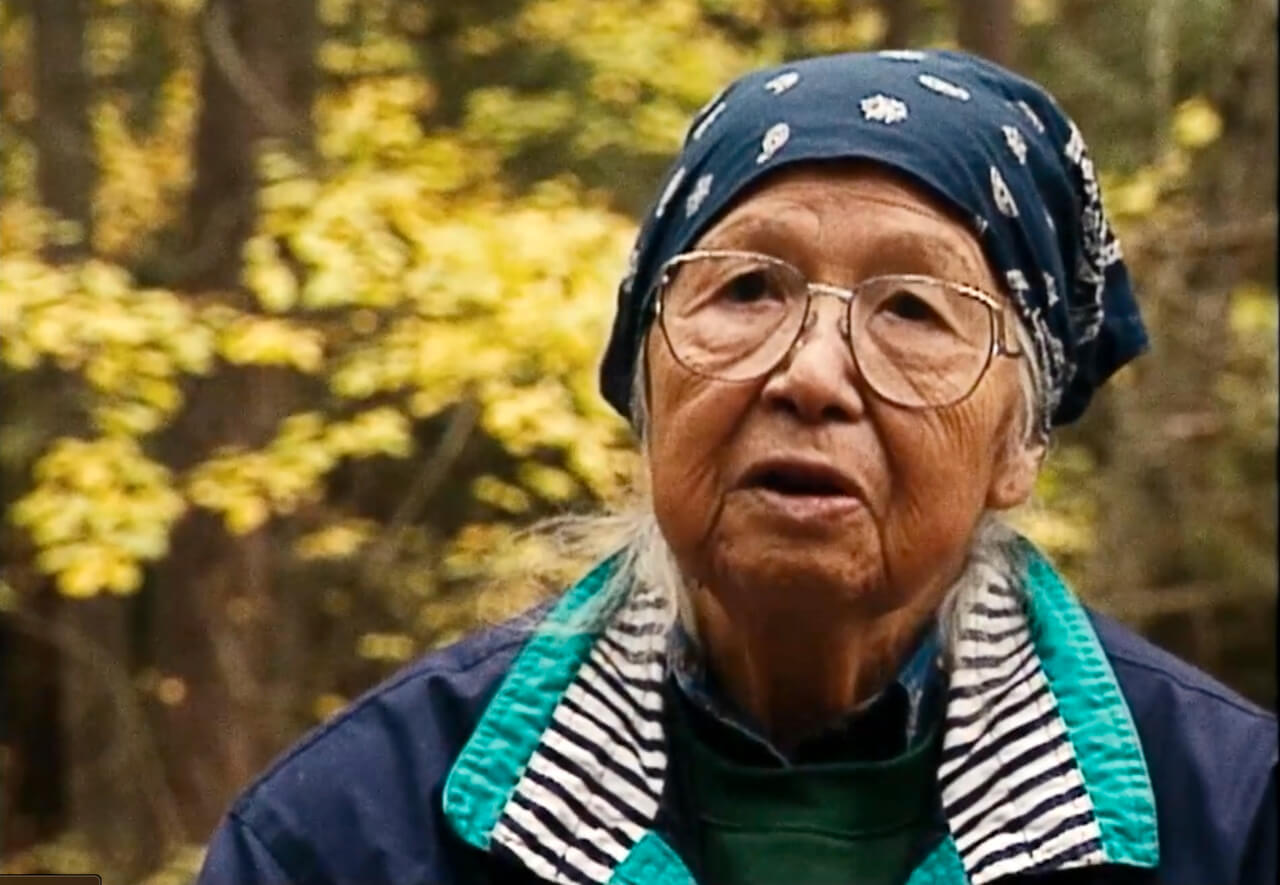

Matriarch Marilyn James, of the Autonomous Sinixt. Image credit: Louis Bockner.

Beyond Extinction: Sinixt Resurgence

100 minutes, English, Snslxcin, 2022

Writer, Director, Producer: Ali Kazimi

Share Article

First the river, in first light or perhaps last. Its current a barely perceptible movement. At its edges it runs indigo – a thickening churn to the banks shrouded in shadow then beyond to the depthless conifers and undergrowth – all brooding charcoal then layers of darkness. Along its spine the river is a gash of mottled glittering silver - gathering cloud whisps across its surface – a gently breathing shiver through the landscape. There’s bird song – a late dawn chorus – or the plaintive calls of twilight – haunting. Then a series of monochrome frames unfold like the landscapes of a Song-dynasty scroll, snow-capped peak and a stand of trees – a blue jay’s call piercing the stillness. Then a mountain comes into view – backlit by a swatch of asymmetric sunlight - the frame dipped in cobalt – a cyanotype – that distorts the co-ordinates of time and space.

You could be anywhere. Anywhere where there are trees and mountains and a river snaking its way through what seems like a pristine, unpeopled landscape – at any time.

Then the filmmaker’s voice pulls you out of your revery – but gently so, liltingly. He tells you that “this is a film about a ghost people who live in a ghost territory”. Amidst and through a series of dissolving landscapes – autumnal and wintering, water, thickets and foliage - he elaborates on that single haunting fact: “this is a story of the seizure and partitioning of their land by two colonial powers. It is a story of a people declared extinct”.

The anywhere yields to specificity. You are somewhere. The filmmaker tells you that you are somewhere. The place has a name - the river – a name – the lakes can be named – their waters traced on a map - therefore the people can be named but the naming itself, it turns out, is contested – contestable: Arrow Lakes – the Sinixt – a cross-border people. It turns out that a stroke of a pen can render the people who people a landscape contestable; their burial sites can be exhumed and rendered contestable; and their bones archived by museums and rendered contestable, and their language subjected to a taxonomy that can render it contestable; stories, myths, presence – all of it contestable. That’s what colonial policies can do. That’s what they are designed to do.

When we first see Marilyn James – Sinixt Matriarch and the ferocious, beloved, beating-heart of this film, she is picking soapberries. It’s a simple act. She plucks the ruby-like flesh from the stalks of the plant and drops them into a container – as her mother might have done, and before that, her grandmother. Occasionally she slips a berry into her mouth – delighting in the secretive pleasures of an acquired taste. There is continuity in the act. A material reality in defiance of the colonial contestable. Later, seated amidst a stand of trees she tells us “when we began occupying this site, here at Vallican, it was always about the responsibility of the Sinixt people to this territory, this tum-ula7xw”.

This is a film that counters the contestable.

In truth it could only have been made by someone like Ali Kazimi: “an immigrant from India, now a Canadian citizen” who feels “complicit with the ongoing legacy of creating a colonial white settler state”. He tells us this, having first told us of his earlier journey to the territory of the Sinixt. He had gone there in 1995 with resources for a few days of filming – an archived collection of video tapes is what remains of that time – the images and voices and memories of those who have passed on or drifted away – taking with them slivers of the past – language and story. Kazimi, poignantly reflects on this past and on the distinction between what is remembered and what is recorded – and on the necessity of resisting amnesia, “an amnesia, as he puts it, that is necessary for any colonial process”.

The genius of this film is the way in which it seamlessly layers and frames the past and the present – less chronology than archaeology – perhaps. And the way in which it keeps returning to the elemental certainty of the waters and the trees, the stones and mountains and the voices of the Sinixt elders with their own elemental certainty – carrying sound and myth through time.

Half-way through the film a young Marilyn James walks us through the landscape of her familiar. She’s talking to Zool Suleman, the South Asian lawyer the Sinixt have hired to deal with the case of Robert Watt. Marilyn James is in her element - amidst the trees, beside the river. She pauses for a moment and then begins to speak:

“when I come here, I feel that I get to observe history that happened hundreds of years ago possibly thousands of years ago. I don’t have a right to take it away from here, but I get this gift to actually see it and observe it and touch the tools that they touched and…you know feel that presence here. I can feel the rock where the grinding took place, and in my mind see some woman, you know, grinding up and making cakes and singing her songs, you know, and that just fills me up…”

I thought about her words long after the film ended – thought about them as the perfect description of how I felt as I left the screening room and plunged back into the flow of the city - with its artificial light and disappointments. The film had ground away at the embodied self as well – I could feel the surfaces where the grinding had taken place - whittling away my assumptions and what I thought I knew about this land and the histories of place.