Bead Me Up Scotty!

Radical Stitch at the Eiteljorg Museum reviewed

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon #125340

Radical Stitch

April 12, 2025 – August 3, 2025

Eiteljorg Museum

Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Curated by Sherry Farrell Racette, Michelle LaVallee and Cathy Mattes

Organized and Circulated by The MacKenzie Art Gallery

Share Article

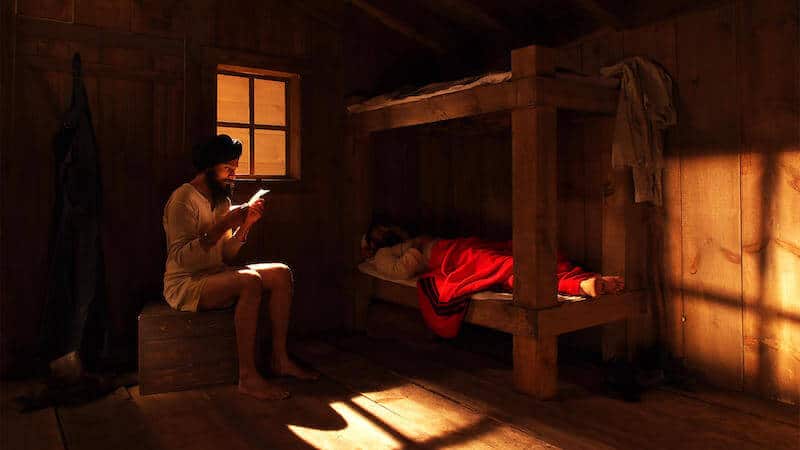

Arriving in Indianapolis on a blisteringly sunny day in July, I feel suddenly and belatedly that I’ve finally landed in the American Midwest. After living in Chicago for three years, a place I jokingly call “Big Edmonton” to my friends, it isn’t until I get off the plane to Indianapolis, that I feel, for the first time, an experience of the American heartlands—and a disorienting nationalist alienation. My trip will be brief. I’m only here a day and a half to visit the Eiteljorg Museum for the last leg of the touring exhibit on contemporary Indigenous beadwork, Radical Stitch. Somehow the tight timeframe doesn’t stop me from accidentally getting plastered at 6:00 pm from a mere two drinks, after wildly underestimating the liberal pour of Indy bartenders, and then spending the rest of the evening sobering up with bar mix and jazz at the Chatterbox.

Amidst the veritable desert of national arts funding in America, the Eiteljorg is a relative anomaly. Prior to my trip, while flirting shamelessly with an installer from the gallery at the Chicago Art Expo, I learned that the museum offers yearly competitive grants to fund contemporary Indigenous arts through the Eiteljorg Contemporary Art Fellowship. The fellowship includes unrestricted funds to support creating work and future funds towards purchasing a portion of those completed works for the museum’s permanent collection. I mention this to plug the fellowship to our Canadian readership (who might take advantage of this considering how successful Canadians have been with applying in the past), and to underline the relative oddity of this space in a national context where Indigenous arts are routinely marginalized.

Radical Stitch is a phenomenal show. Correctly nicknamed “the Big-Ass Beading Show” by its curators Sherry Farrell Racette, Michelle LaVallee, and Cathy Mattes, the exhibit is massive, representing fifty-two Indigenous artists from across North America (17). 1 Flipping through the catalogue, it’s obvious not all the works from the original show made it to Indianapolis (probably due to spatial constraints) but it was still impressive, even in its abbreviated form. As an amateur beader, I was overwhelmed by the sheer scale and ambition of the pieces. Even the smallest works in the show must have taken at least a hundred hours to design and produce. Consider, also, the exorbitant costs of production (beads ain’t cheap) and suddenly every step in the exhibit feels as if you are walking amongst giants. In this review, I’ll be talking about the pieces that provoked the most thinking from me rather than attempting to judge the best or most impressive.

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon #125238

I was thrilled to see Jamie Okuma’s Fright Night (2019) in person after many years of admiring it from afar. Using microbeads Okuma recreates realistic versions of scenes from Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula (2000) and Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991) on a leather bag and wallet. While I’ve seen her caribou boots before at the textile museum in Denver (and they were great there), these objects are truly electric. First, let me confess that part of my love of Fright Night is sentimental. They remind me of a much younger me: a horror-obsessed high school goth, bespectacled and dog collared for many of her formative years. In person, however, it is obvious the works are also conceptually rigorous. Made to be attached to a belt, the beadwork on the front of the bag depicts the vampire Lucy screaming. In the context of Coppola’s film, Lucy has just returned to her mausoleum when she is confronted by her fiancée who has come to murder her. “Come to me, Arthur,” she moans seductively before Van Helsing abruptly shoves a crucifix in her face, which forces her screaming back into her coffin where they stake and behead her. In the next scene, Coppola juxtaposes Lucy’s dead head arcing through the air with Dracula’s furious realization that his newest progeny has died. Okuma’s bag appears to represent the scream and the beheading simultaneously. The image depicts an undead Lucy in all her glory while the spikes along the bag’s edge and the closely cropped image of Lucy’s head suggests her final end. The bag’s ability to conjure all these different moments and collapse them into one made me highly attuned to how beadwork plays with time and space in the rest of the exhibit.

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon #125340, #125347, #125352

The wallet performs another kind of representational labour: Okuma takes images of two villains from the same film (Hannibal and Buffalo Bill) out of context and sets them both on an opaque yellow background. These stills come from scenes in Silence of the Lambs when these characters seem to me most “themselves”: when Hannibal pausing to listen to Glenn Gould’s “Goldberg Variations” before murdering his guards and when Buffalo Bill dancing to Q Lazzarus’ “Goodbye Horses” in front of a mirror while wearing a wig of human skin and women’s clothing. The music draws viewers into their fantasy space. Both are moments of repose and meditation where the film rests to explore the sensuous, aesthetic qualities of violence and murder. While newer versions of the franchise (the absolutely garbage Ryan Murphy television series) have exhausted this aspect of the original film/book, rendering its insights nearly meaningless, Okuma’s beadwork restores some of the original eeriness of the story by imaging them as still portraits that freeze the viewer in their reveries.

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon 124916, #124925, #124929

While moving through the show, I spent a lot of time thinking about beadwork and film. Both mediums shape time and space though the connections between them are slightly less obvious than film and comics, wherein the durational quality of the mediums seems self-evident. For instance, there is a working screen in the center of Barry Ace’s Bandolier for Alain Brosseau (2017) that contains a slide show of images and text explaining the hate crimes that led to Brosseau’s untimely death. Ace’s screen appears pixelated because there is a mesh sewn overtop of it, which makes the viewer see the similarities between the tiny pixels that comprise each image of film and the individual beads that comprise the decorative floral beadwork. The moments leading up to Brosseau’s death are catalogued and represented through images and title cards that explain where he died and the granular detail of the homophobic attacks against him. In Sculpting Time, Andrei Tarkovsky describes the “artistic image” on film to be a “detector of infinity” that affects us by drawing moments in time together in an experiential way: “Such a feeling is awoken by the completeness of the image: it affects us by this very fact of being impossible to dismember. In isolation, each component part will be dead—or perhaps, on the contrary, down to its tiniest elements it will display the same characteristics as the complete, finished work” (109). Like the frames of a film, each bead, in isolation, is somewhat inert but the act of linking them together produces an image. The work of tacking each little glass orb (one or three or five at a time) to leather, fabric, or other material is like the slow accretional quality of editing film. When done well, it is as if, as Tarkovsky says, “time itself, running through the shots, had met and linked together” (117). In the context of Ace’s work, the literal connection of beadwork and film allows him to do the memorial work necessary to render the absence of Brosseau immaterially present. Each frame and each bead seek to restore the broken image of the long dead in a processional mode that is monumentalized on the bag itself.

Ruth Cuthand’s video Mark of a Woman (2019), created in collaboration with her son Theo Cuthand, is an incredible ode to beadwork’s ability to tell stories beyond the point of death. In this video, Cuthand tells a story about visiting a shack on the edge of a reserve in Alberta as a child. This building, she explains, was a place where bodies used to be kept before burial. In the shack, she remembers seeing skeletons in wooden boxes, still unburied. As she speaks, viewers see an image of a rock in the grass under bright sunlight. Offscreen someone is pouring beads onto the rock, causing them to bounce around in the light, forming a colorful halo around the rockface. Outside the shack, Cuthand recalls seeing a bedframe where someone had also been laid to rest, except that it had been so long that the land had taken all the parts of the bed and the body away except a small heap of beads where the head would have rested and the mattress springs. As Cuthand speaks over the image of the dropping beads, the rock seems almost like a face looking out at the viewer, beautifully still as the beads jauntily spring about, framing her opaque head, which seems to sink into the land. In his masculinist ode to the “camera eye,” Stan Brakhage compares the film image to a beaded womanly shape that appears silhouetted in light: “Oh transparent hallucination, superimposition of image on image, mirage of movement, heroine of a thousand and one nights (Scheherazade must surely be the muse of this art), you obstruct the light, muddie [sic] the pure white beaded screen (it perspires) with your shuffling pattens” (121). While Brakhage lazily reproduces the common adage of phallic lens and feminine image, Cuthand uses film to represent the impossible miracle of witnessing “the mark of a woman” on the land through the vestigial, remnants of her beauty and labour, which persist in each bead that lays astride the rock.

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon #123234, #132609, #132625, #132635, #132650, #132658, #132705, #132714

Other pieces in the show also spoke to the durational nature of beadwork and the sacred time of its practice. Faye Heavyshield’s beaded book hours (2007), for instance, is open onto a what looks like a series of blank white pages. It seems to ask, is beadwork a kind of inarticulate writing? Transparent as the page, it can be read but not without being translated. Heavyshield’s work sits next to Skawennati’s wampum piece Intergalactic Empowerment Belt (Onkwehón:we, Na’vi, Skyworlder, LGM, Overlord) (2017), which I think was an inspired curatorial choice to get viewers thinking about the complex interpretive demands that beadwork asks of us. Wampum belts often have dedicated “keepers” who are responsible for carrying and interpreting the belt. Skawennati’s wampum belt imagines a future treaty with alien civilizations but no “keeper” appears forthcoming. As viewers, are we the ones responsible for these interpretations? Near the back of the exhibit, behind Heavyshield and Skawennati, sits Judy Anderson’s ode to Maria Campbell And from her parts of me emerged… (2016). A full fox skin sits curled in a giant beaded version of the newest edition of Maria Campbell’s memoir Halfbreed (1973) almost like a sleeping cat. In the accompanying panel, Anderson explains that the piece represents the “part of her[self]” that emerged from her friendship with Campbell, which began for Anderson while reading her book. A relationship between two people often has a life of its own and the little sleeping fox spoke to me as a beautiful and joyful representation of Anderson and Campbell’s.

Image Credit - Madeleine Reddon #123530, #123638, #123654, #123708

Everytime I think of you I cry (2021) is another work by Anderson in the show that commemorates an important relationship in her life. This piece is an enormous, beaded curtain made from varying shades of white translucent and transparent beads that hangs off a long wooden dowel. Piles of porcupine quills are pooled below the beaded tendrils along the ground like a little trail of animal detritus. From afar, this viewer can see that the piece spells out the name “Eugene” but as I get closer the lettering becomes more difficult to see and I begin to see instead gentle gradations in the translucency of the beads, which resemble long arcing waves. There is also one tiny red spirit bead in the piece that I could not find. Created by Anderson’s entire family to “commemorate their loss” (Eiteljorg), Everytime I think of you I cry honours Anderson’s brother who was taken in the Sixties Scoop by re-imagining the kitschy 1960s beaded curtain as a memorial object. Anderson simulates the weight of grief by using beads to evoke the transparency of tears. The beautiful swoops that link each individual strand seem to simulate the waves of grief. Standing there, a bit overcome, I feel a strange desire to walk through the curtain. What will be on the other side for me? Why do I feel such a strong wish to touch this piece? Each bead a moment of pain felt and released, strung up like a glorious and heartbreaking representation of many hearts being hurt and healed, Anderson has created a visceral image of the weight that relationships take in our lives.

References

Brakhage, Stan. "Selection from Metaphors on Vision", in The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 1978), pp. 120-128.

Racette, Sherry Farrell, and Michelle LaVallee and Cathy Mattes. Radical Stitch, MacKenzie Art Gallery exhibit catalogue, 2024.

Tarkovsky, Andrey, and Kitty Hunter-Blair. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. University of Texas Press, 1989.

-

From the MacKenzie catalogue (a gift I received courtesy of Pulpfiction). Page numbers cited are from the catalogue.