Beneath Sunny Surfaces

Diffuse Desire in Durga Chew-Bose’s Bonjour Tristesse (2024)By Rebecca Peng

Bonjour Tristesse

Written and directed by Durga Chew-Bose

Starring Lily McInerny, Chloë Sevigny, Claes Bang, Naïlia Harzoune

Now streaming

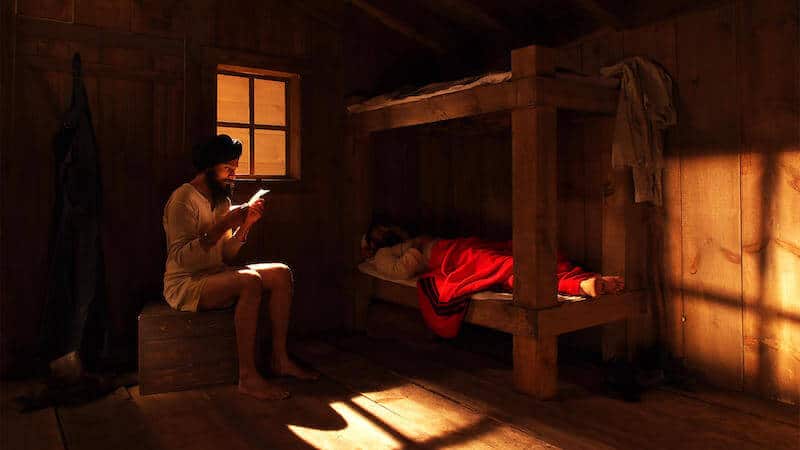

Image Credit: Greenwich Entertainment – Bonjour Tristesse (2024)

Share Article

First published in French in 1954, Bonjour Tristesse was a runaway success. The story follows precocious seventeen-year-old Cécile and her wealthy, rakish father Raymond as they holiday on the French Riviera. Over the summer, Cécile is confronted with both sexual and moral awakenings. Within a year of Bonjour Tristesse’s publication, a 1955 English translation led The New York Times bestseller list. Françoise Sagan, who had written the novella when she was a precocious teenager herself, was the youngest author to top the NYT bestseller list at the time.

Durga Chew-Bose, who both wrote and directed this latest adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse, also comes to the film by way of runaway literary success. She was asked to adapt Sagan’s novella because of her 2017 breakout essay collection, Too Much and Not the Mood. Roving and digressive, Too Much and Not the Mood excelled at atmosphere; it remains a capsule of an exemplary 2010s style.

This attunement to simmering moods guides Chew-Bose’s film, which won its director TIFF’s Emerging Talent Award. In the original novella, Cécile has acclimated to her playboy father, who scandalously rotates lovers “every six months.” At the beginning of the summer, Raymond’s “mistress of the moment” is twenty-nine-year-old Elsa Mackenbourg, indistinguishable from so many young women frequenting “the studios and bars of the Champs-Élysées.” Their holidays are upended when Raymond invites Anne Larson to join them. At forty-two, Anne is Raymond’s contemporary—and entirely singular. Anne is fashionable, poised, and demanding. Cécile is equally awed by and resentful of Anne and the more mature, disciplined life she represents.

Raymond’s affections quickly shift from Elsa to Anne, who brings order into Cécile and Raymond’s lazy bacchanalia. She forces Cécile to study for her exams and impedes Cécile’s burgeoning sexual affair with the neighbouring Cyril, a twenty-something law student with, Sagan describes, “typically Latin” good looks. Fearful of these changes and protective of her independence, Cécile plots against Anne, convincing Cyril and Elsa to pretend to be lovers in order to stoke her father’s jealousy and tempt him back to Elsa. Only belatedly does Cécile recognize Anne’s vulnerability and humanity—but it’s too late to avoid the consequences of her callous plotting.

In her modernization, Chew-Bose is as stylish in film as she is on the page. Bonjour Tristesse (2024) has a sophisticated and beautiful visual language, speaking through bright saturations of primary colours: ocean blues, sunny yellows, and shocking reds. Working with costume designer Miyako Bellizzi (Good Time, Uncut Gems), Bonjour Tristesse conjures a stylized world that never sheds its tactility. Object interactions are deft and revealing. When Anne arrives, Cécile self-consciously corrects her inside-out top, belatedly making herself more presentable. Later, Anne gifts Cécile a stunning gown. Chew-Bose adds texture to this extraordinary gift and realism to the feelings it raises in Cécile: we see her sitting before an open refrigerator, spreading the dress skirt and privately preening in the fluorescent light while her family sleeps. There are striking tableaus of objects and foods, bold slices of citruses. On small, affecting occasions, Cécile takes and reviews photos of herself, documenting her burgeoning adulthood. In a study of contrasts, Elsa and Cécile eat lawlessly with their hands, while Anne (Chloë Sevigny) methodically eats apple slices directly off her knife.

Chew-Bose also excels at depicting domestic intimacy, most especially between Cécile (Lily McInerny, with a perfect balance of youthful insecurity and invulnerability) and Raymond (Claes Bang), as they crowd a couch to play solitaire together or chat into the night. Chew-Bose shoots one of their conversations in the dark, shifting from one profile to another as though tossing audiences onto either side of a coin, an ingenious way of demonstrating the bond between father and daughter. Throughout Bonjour Tristesse, the actors occupy scenes with a lived-in ease.

But Chew-Bose’s adaptation falters, slightly, when it comes to Cécile’s love plot. The age differences which are so crucial to the stakes of the novella fail to translate on screen. Marketing materials underline that Cécile is a somewhat less scandalous eighteen-year-old, and Cyril (Aliocha Schneider) appears more or less the same; the gulf between high schooler and college student is no longer palpable. Nor is Elsa the shallow twenty-something she was on the page. Naïlia Harzoune plays Elsa with such captivating poise that she reads as a peer to Anne instead of a silly foil. The film’s alterations to the characters’ nationalities also shifts the tensions of Sagan’s novel. No longer is there a divide between different Parisians; here, Raymond and Anne are expats, sporting British and American accents respectively (Cécile, like Anne and unlike her father, has an American cadence). Elsa is fabulously international, boasting relatives across Europe and beyond, while Cyril is now French, dulling any cultural differences between himself and Cécile; their families dine happily together while encouraging Cyril and Cécile’s romance.

In the novella, Cyril and Elsa’s apparent affair wounds because they are appropriate for each other, their union testing both Raymond’s and Cécile’s shifting desires around stepping into adult responsibility. Constantly, the film shies away from asking questions about “proper” matches. Its internationality does not introduce new tensions but rather continues this diffusion of specificity. None of the differences matter. The love affairs feel weightless and arbitrary. By sanding down the nuances of age and nationality, the film loses the core frictions that make its plot impactful.

We lose, too, some of the complexity between Cécile and Anne. There’s less time for what attracts Cécile to Anne, and for the empathy Anne shows Cécile when she believes Elsa and Cyril have come together. Instead of Sagan’s sensitive portrayal of fearing something that might, in fact, be good for you, we have a story of semi-straightforward teenage rebellion. This isn’t from a lack of skill from the actors (Sevigny has a particularly affecting moment at the film’s climax); it’s the script that speeds along the surface of their connection.

Bonjour Tristesse is a story of superficial people, but it penetrates in subtle, subversive ways. Chew-Bose is not a stranger to negotiating cultural contexts. In “D As In,” an essay from Too Much and Not the Mood, Chew-Bose reflects on balancing her “parents’ Indian heritage with [her] own Canadian childhood” and the perils of compromising her own racial specificity in casual social interactions. It’s certainly unfair to hold any artist to something they produced a decade ago, but “D As In” raises still-pertinent questions around balancing one’s cultural inheritances—questions that might have further enriched her film. The characters can be any nationality one pleases, but Bonjour Tristesse’s narrative hinges on engaging with, rather than downplaying, the relationship between desire and difference.

Ultimately, Chew-Bose brings the film back to those beautiful surfaces. In the final scenes, Cécile telegraphs her longing for Anne by dying her hair from its original brunette to Sevigny’s blonde. Chew-Bose transmutes the novella’s final, ruminating chapter into dialogue. When Raymond wonders aloud whether he and Cécile will be happy again, Cécile’s response is weighted with melancholy: “But we will.” She goes to a party and shyly greets her new love interest but becomes immobilized in the coatroom. At every turn, her loss is made external. For me, the affecting qualities of the novella reside in the opposite: in its observations of how happiness can rush along, eroding even the most profound tragedy into an afterthought.

Still, none of these qualities undermine the wonderful performances or Chew-Bose’s artful direction: the lived-in vistas, the casual arrangement of breakfasts, the sublime seasides Cécile tentatively toes along.

At the beginning of the film, Raymond and Elsa watch Cécile at the water’s edge. When Cécile poses and shifts her angles, Elsa observes that she’s practicing “for when she wants to be seen.”

“No,” Raymond’s despair is jovial. “I’d rather not think about my daughter being looked at.”

“I said ‘seen’ not ‘looked at’,” says Elsa. “It’s a feeling. It’s like a power.”

Bonjour Tristesse knows this power. One leaves eager to see where Chew-Bose will direct her talents next.